Index

This was a day that I dreaded to see, even though I knew it was inevitable.

Standing in the checkout line at Trader Joe's, I looked at the BBC News website on my phone to see what was happening in the world. The inevitable had happened.

"How you doin' today?" the young woman asked as she pulled in my cart.

Standing in the checkout line at Trader Joe's, I looked at the BBC News website on my phone to see what was happening in the world. The inevitable had happened.

"How you doin' today?" the young woman asked as she pulled in my cart.

"I was doing pretty well until I just found out that Chuck Berry had died." Even as I said it, I knew I sounded like an old guy—that was probably a name her grandparents knew.

"Yeah," she began uncertainly. "We've had a lot of deaths lately."

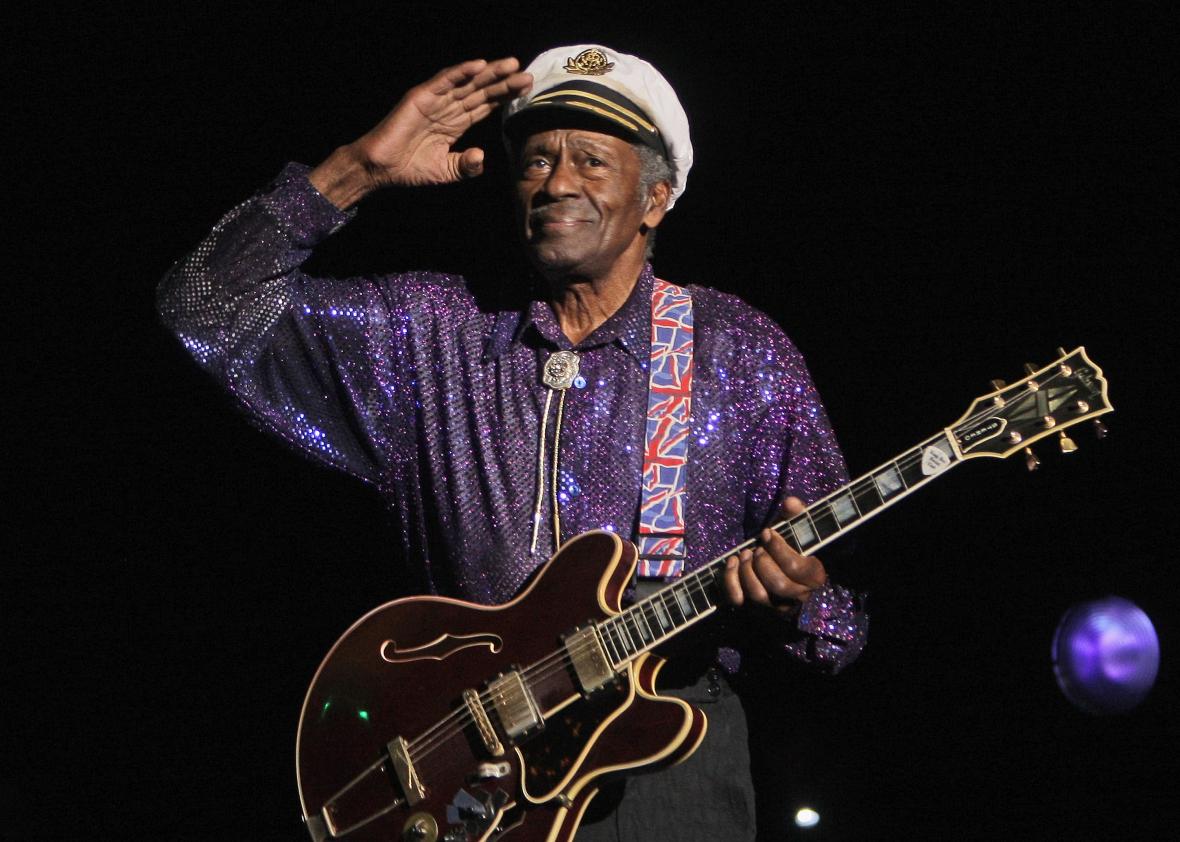

Chuck Berry died on March 18, 2017, at the age of 90. He certainly lived a long life, a colorful life, and as the Architect of Rock and Roll, an indispensable life.

Yet exemplifying the resilience that marked his life, Berry announced on his 90th birthday last October 18 that he would be releasing his first album of new material in 38 years. Chuck, slated to be released on Dualtone Records sometime this year, is dedicated to his wife of 68 years, Thelmetta, and features his son Chuck, Jr., and daughter Ingrid on guitar and harmonica, respectively.

In case you've just arrived from Alpha Centauri and need to get up to speed, Charles Edward Anderson Berry is one of the Founding Fathers of rock and roll music, which is a lot like saying Albert Einstein was one of the leading scientists of the 20th century. It is not a case of first among equals—it is very much a case of Berry being in a class by himself. Well, I'm sure he wouldn't mind the company of a nubile co-ed or three in that classroom, but we'll get to that by and by.

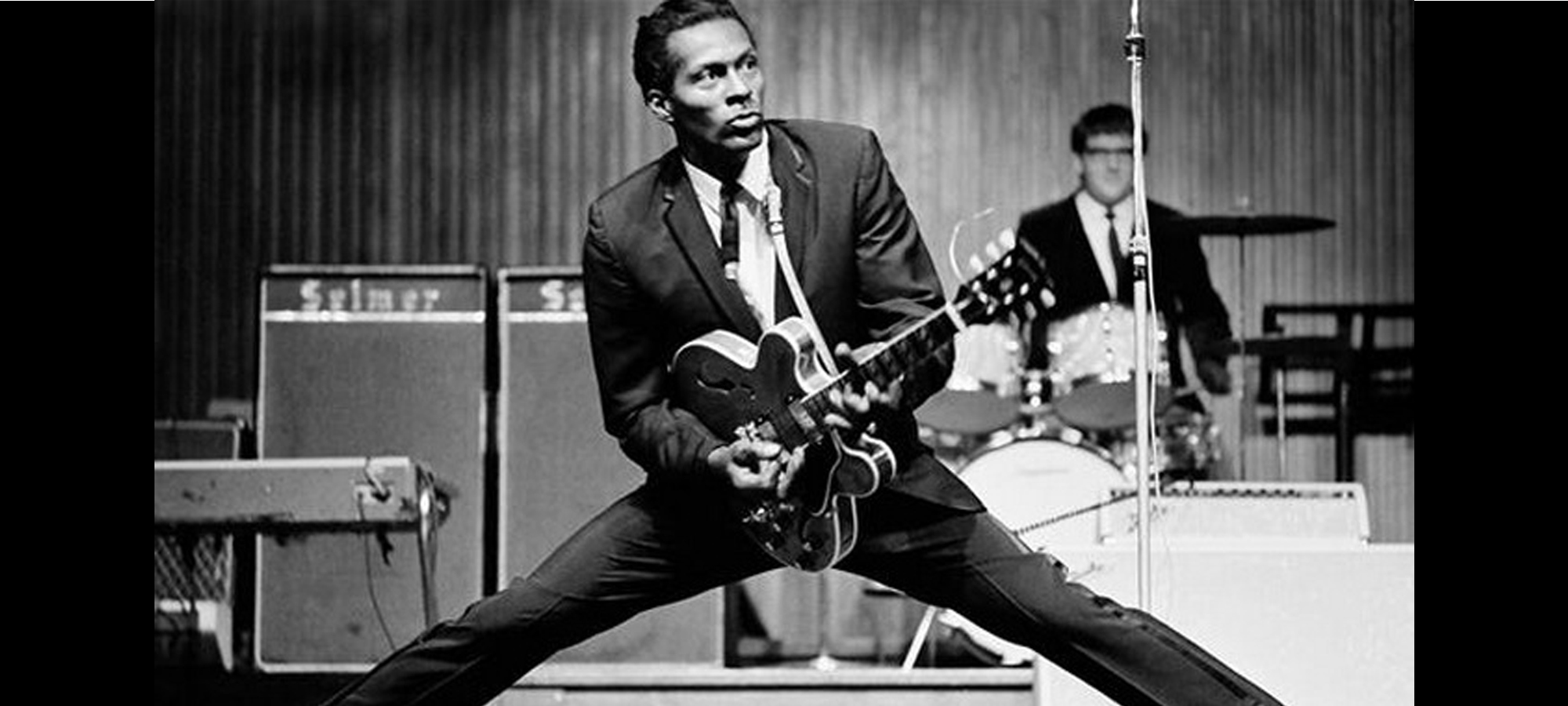

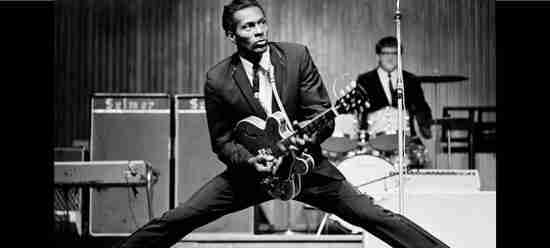

Amidst the swirling streams of various musical forms—primarily blues, rhythm and blues, and country and western—that were beginning to cohere into rock and roll by the mid-1950s, singer and guitarist Chuck Berry assimilated them all into a distinctive sound while adding attitude and showmanship cribbed assiduously from jump-blues star Louis Jordan and flashy blues guitarist T-Bone Walker and, most importantly, his astute observations on love and lust and the carefree mood of a prosperous post-World War Two America that inflamed the imaginations of countless teenagers not only in the United States but around the world.

Chuck Berry derived his dynamic onstage showmanship in part from blues guitarist T-Bone Walker.

Ironically, Berry was nearing 30 and already a married man with two young daughters when he recorded "Maybellene" for the Chicago-based blues label Chess in May 1955; significantly, "Maybellene" was an adaptation of the country song "Ida Red," last popularized by Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys nearly 20 years previously, with Berry fusing sex and automobiles into an evocative metaphor atop his fast, ringing guitar rooted in the blues playing of Walker and Chess Records superstar Muddy Waters. "Maybellene" topped the Billboard Rhythm and Blues singles charts and reached Number Five on Billboard's Hot 100 singles charts as Berry helped to buoy Chess's flagging fortunes, and from then on Chuck was in business.

Yet even at that point Berry was a study in contrasts. Born into a middle-class African-American family in St. Louis, Missouri, Berry developed an early interest in music, and given St. Louis's cosmopolitan location at America's crossroads, he grew to appreciate a variety of musical forms—Nat "King" Cole was an abiding influence as a singer, for instance—and he was already playing guitar by his teens. However, in 1944 he was convicted of armed robbery and spent three years in a reformatory before being released on his 21st birthday. He didn't let being incarcerated stop his musical interests, though, as he formed a singing group while serving his time—and serving time would become a leitmotif for Berry throughout his life.

A year after his release, Berry married Thelmetta, and a year after that Ingrid was born. To support his family, Berry worked various jobs, including a janitor and auto worker before attending cosmetology school to become a hairdresser, while playing in a number of local St. Louis bands to supplement his income. By 1953, he began playing in pianist Johnnie Johnson's band, which marked the start of a long association with this crucial collaborator, as he perfected his fusion of R&B and country and western with a combination of Cole's vocal style and Waters's guitar influence before he cut "Maybellene" two years later.

All of which was merely capsule description when I read about it in my teens, in the first book I ever bought about rock music, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock by Nick Logan and Bob Woffinden, which has survived numerous moves, mishaps, and maulings to remain sitting, battered but unbowed, on my bookshelf today.

That book was my first education on rock music; I read it so religiously that indeed I referred to it as my rock bible. And having read so many times the entry on Chuck Berry, which began, "One of the enduring legends of rock 'n' roll, and its single most influential figure," I knew it was only a matter of time before I explored his music. Many years later, my discovery of Chuck Berry's music remains a milestone in not only my musical education, but in my life.

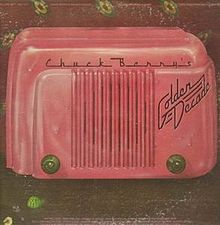

I must have been about 19 or so when I bought my first Chuck Berry album. It was the Chess anthology Golden Decade, a two-LP set first released in 1967 although my later pressing had been "altered electronically for stereo," an artificial process that added crappy fake stereo to the original mono recordings. At that time, I was hardly an audiophile—besides I was listening to what the songs were saying, not to how they were presented.

And what songs. From the moment the needle dropped on the opening track, "Maybellene," I had the sense that I was getting to the core of how rock and roll started. The next track, "Deep Feeling," was an instrumental that seemed middling and in retrospect is the album's only dud; tellingly, "Deep Feeling" is the only track from Golden Decade not included on the 1988 three-CD boxed set The Chess Box.

But any sense of disappointment or apprehension was wiped off the map by the next song. From the opening burst of brash, staccato guitar notes that introduced it, "Johnny B. Goode" leaped off the turntable to grab me by the balls. Holy shit—this was the essence of rock and roll! I'd discovered the Holy Grail! Granted, the next song, the wistful ballad "Wee Wee Hours," was a deliberate chill-out that took me a few years to appreciate.

But then we were back to rock and roll with "Nadine," which swung so hard it almost hurt, but from the first listen I was enamored by the lyrics, which was the coolest story I'd ever heard (or so it seemed). It was then that I realized what a great storyteller Chuck Berry was; "Nadine" became the first of his songs I learned by heart—indeed, by now I was "campaign shoutin' like a Southern diplomat" when it came to digging Chuck Berry. That "deep feeling" continued into "Brown-Eyed Handsome Man" and more magical lyrics right from the start: "Arrested on charges of unemployment/He was sittin' in the witness stand/The judge's wife told the district attorney/'You better free that brown-eyed man/'You want your job you better free that brown-eyed man.'" It wasn't too long before I adopted that as my theme song because—all right, I'm a man, and I do have brown eyes, but I'll leave the handsome part to the judgment of the observer.

I was hooked. And I hadn't even flipped over the first record yet.

The "textbook" for my education on Chuck Berry: Golden Decade (Chess Records, 1967). Crappy fake stereo be damned.

Needless to say, that flip side and the second record contained gem after gem—the wellspring of rock and roll, Chuck Berry division: "Roll over Beethoven," "No Particular Place to Go," "Memphis," "School Days," "Too Much Monkey Business," "Reelin' and Rockin'," "You Can't Catch Me," "Sweet Little Sixteen," "Rock and Roll Music," "Back in the U.S.A.," and so many others.

In truth, I had heard a number of Berry's songs previously through cover versions—the Beatles' renditions of "Roll over Beethoven" and "Rock and Roll Music," for instance, or the Rolling Stones' live cover of "Carol" from Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out!

Perhaps the first one to really grab me was the Yardbirds' live version of "Too Much Monkey Business," from the Five Live Yardbirds album that remains the primary example of Eric Clapton's brief stint with the band that would go on to become Led Zeppelin, although that set has been repackaged so many times, by so many different labels, that I first listened to it on a budget reissue by Springboard Records that promoted the record by putting Clapton's name in the title and putting a 1970s-era photo of the guitarist on the cover. I liked the Yardbirds' sloppy frenzy as they barreled through "Monkey Business" to lead off the set even if Keith Relf's mush-mouthed delivery obscured the lyrics, and it wasn't until I heard Berry's original that I came to appreciate their articulate wit.

Indeed. Of all Chuck Berry's gifts, the greatest may be his lyric writing, which is no small statement considering that by synthesizing disparate musical elements into a distinctive and immediately recognizable sound, he created a musical template that has been endlessly repeated—just listen to the Rolling Stones, who in turn inspired countless bands. And by establishing the electric guitar as the dominant instrumental expression in rock and roll, Berry gave the musical form its singular signature—or as Bob Seger once sang, "All of Chuck's children are out there playing his licks."

And although this may be the bias of a writer, I feel that in the words to his songs, Chuck Berry literally gave voice to what may be called, albeit tritely, the rock and roll sensibility. That sensibility appealed primarily to teenagers, who had relatively few responsibilities, a fair degree of freedom, and the raging hormones and inflated sense of melodrama inherent in post-pubescence. Certainly "School Days," "Anthony Boy," and "Oh Baby Doll" spoke directly to the high school experience, as did "Almost Grown," "Time Was," and "You Never Can Tell," while "Too Pooped to Pop" poked fun at the older generation struggling to stay young by trying the latest dances but inevitably ending up having "gone astray."

Yet "Almost Grown," "Time Was," and "You Can Never Tell," which kicked off with its "teenage wedding," all may start in teenhood but they soon progress into more adult territory, mirroring Berry's own experiences of becoming a young family man. Recorded in 1956 but released in 1957, "Too Much Monkey Business"—now that I could hear what all was going on here—delivers a saga in a shade under three minutes: After making it through school and serving a stint in the army, Chuck's put-upon protagonist gets hitched to a blonde who wants him to "settle down [and] write a book," which means bills piling up and slick salesmen trying to sell him even more while he toils away at a gas station—and even the pay phone takes his dime as he contemplates suing the operator for "tellin' me a tale." Whew! Progressive-rock bands used to take up a double album to convey that much pipe. (Yes, I'm talking to you, Yes.)

Berry's genius for evocative economy reaches its epitome in "Bye Bye Johnny" (1960), the brilliant sequel to his already-epochal "Johnny B. Goode" from two years previously, which furthers the tale of the little country boy who could "play the guitar like he was ringin' a bell" in just over two minutes:

She drew out all her money at the Southern Trust

And put her little boy aboard a Greyhound bus

Leavin' Louisiana for the golden west

Down came the tears from her happiness

Her own little son named Johnny B. Goode

Was going to make some motion pictures in Hollywood

She remembered taking money earned from gathering crop

And buying Johnny's guitar at a broker shop

As long as he would play it by the railroad side

And wouldn't get in trouble he was satisfied

But never thought that there'd ever come a day like this

When she would have to give her son a goodbye kiss

She finally got the letter she was dreaming of

Johnny wrote and told her he had fell in love

As soon as he was married he would bring her back

And build a mansion for 'em by the railroad track

So every time they heard the locomotive roar

They'd be a-standin', a-wavin' in the kitchen door

Optimism and humor buttressed Berry's perceptive eye for individuals and the society in which they pursued their dreams and desires, but he could convey poignancy with the same succinct skill, as the moving "Memphis" (often titled "Memphis, Tennessee"), from 1959, demonstrates:

Long distance information, give me Memphis, Tennessee

Help me find the party trying to get in touch with me

She could not leave her number, but I know who placed the call

'Cause my uncle took the message and he wrote it on the wall

Help me, information, get in touch with my Marie

She's the only one who'd phone me here from Memphis, Tennessee

Her home is on the south side, high up on a ridge

Just a half a mile from the Mississippi Bridge

Help me, information, more than that I cannot add

Only that I miss her and all the fun we had

But we were pulled apart because her mom did not agree

And tore apart our happy home in Memphis, Tennessee

Last time I saw Marie she's waving me good-bye

With hurry-home drops on her cheek that trickled from her eye

Marie is only six years old, information, please

Try to put me through to her in Memphis, Tennessee

"Memphis" was leagues away from the carefree concerns of "You Can't Catch Me," "Reelin' and Rockin'," "'Round and 'Round," and other youth-oriented celebrations—here was the heart-wrenching saga of a father trying to speak to his young daughter, now living with her mother in Memphis, Tennessee, presumably after a separation or divorce that "tore apart [their] happy home." Berry did provide an upbeat conclusion to the melancholy five years later with "Little Marie," which offered a reconciliation once that phone call was finally put through. And why it took five years for the sequel entails Chuck Berry's real-life saga.

By the end of the 1950s, Chuck Berry was established as one of the foremost stars of rock and roll, which was surely here to stay thanks in no small measure to his influence and success, which included hit records, prominent appearances in a spate of rock and roll films such as Rock Rock Rock (1956) and Go, Johnny, Go! (1959), and steady, well-paying concert tours. As a result of his success, Berry opened a club in St. Louis, Berry's Club Bandstand, that was racially integrated, notable in pre-Civil Rights America.

But in December 1959 he was arrested for having sexual relations with a 14-year-old waitress at his club, and because he had transported the girl across state lines, it became a violation of the Mann Act, officially known as the White Slave Traffic Act, which dated to 1910. Berry was convicted and sentenced to a five-year prison term in March 1960; claiming that the judge had been racially prejudiced, he successfully appealed the conviction—but he wound up being retried and convicted once again, this time sentenced to a three-year prison term.

However, when Berry was released in October 1963, he discovered that his music had served as a formative influence on numerous rock artists—indeed, Chuck Berry's impact can be felt in four of the biggest artists of the 1960s: Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Rolling Stones, who are inconceivable without Berry; the Stones' first single was a cover of Berry's "Come On," the last single Berry released before going to prison.

The Beach Boys re-wrote Berry's "Sweet Little Sixteen" as "Surfin' U.S.A.," one of their landmark songs—generating contention with Berry over authorship credits, at least initially—while maintaining that style in much of their early material. When Dylan, who had fronted a rock and roll band in high school, "went electric" to help create folk-rock, he used the swing and drive of Chuck Berry's rock. And the Beatles helped to popularize Berry's songs to a new generation; John Lennon once said, "If you tried to give rock and roll another name, you might call it 'Chuck Berry.'"

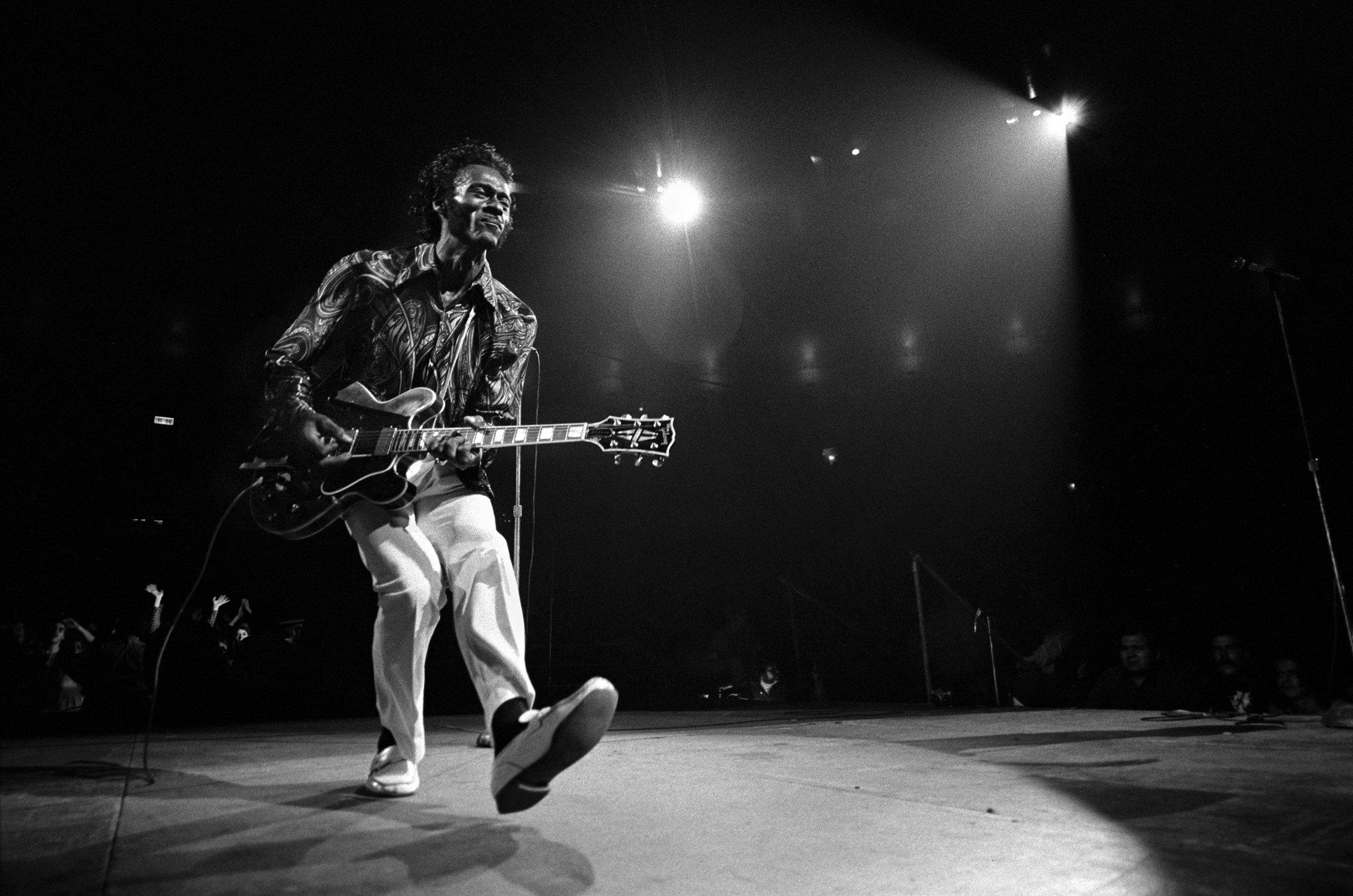

Chuck Berry duckwalks into rock history as the Architect of Rock and Roll. Yet offstage troubles sometimes sullied his image.

Into that acclaim Berry released St. Louis to Liverpool in 1964, arguably the greatest of Berry's studio albums headlined by the delightful "No Particular Place to Go," "Little Marie," "You Never Can Tell" (later used to memorable effect in the 1994 film Pulp Fiction), and "Promised Land," another Berry tale of expansive optimism—all the more remarkable for coming after his criminal convictions—later covered by Elvis Presley, whose version is what Tommy Lee Jones bops his head to in the 1996 film Men in Black. And while "No Particular Place to Go" took a sly swipe at tougher seatbelt laws recently passed for automobiles—Berry's narrator takes his girl to a make-out spot but cannot get her seatbelt unfastened—the melody sounded familiar: This was merely "School Days" redressed, and in fact Berry made no bones about recycling his own melodies and licks, let alone others' that, consciously or not, he incorporated into his songs.

But to return to Berry's Mann Act violation, it ushered in a disturbing aspect to the Chuck Berry persona—that of a ephebophile or even a hebephile (indicating an adult with a persistent sexual interest in children in late- or early adolescence, respectively; although the term pedophile is commonly used, it more properly refers to prepubescent children). In the 1990s, Berry was charged with videotaping numerous women in the restroom of the restaurant he owned, and one of those was a minor, although when authorities raided Berry's home they found videotapes of several underage girls in sexual poses.

That puts some of his best-known songs into a troubling perspective, particularly the aforementioned "Sweet Little Sixteen," in which Berry paints the star-struck young heroine in "Tight dresses and lipstick/She's sportin' high-heeled shoes." Similarly, the object of his desire in "Little Queenie" is "too cute to be a minute over seventeen." Sung by a teenage boy, those observations seem appropriate—but Berry himself was already a thirtysomething, and the narrator of "Little Queenie" is first-person. Dare we speculate on "Sweet Little Rock and Roller," who is just nine years old and "never gets any older." Not to put too fine a point on it, but the term "rock and roll" used to be a slang term for fucking.

About all of which I was blissfully ignorant when I began to wear out my copy of Golden Decade way back when. Returning to the record store, I found a copy of Golden Decade, Vol. 2, a French import copy that cost more than the first volume but at least all the songs were in pristine mono even if the two LPs weren't as power-packed as the first set. Still, there were several signature songs here ("Carol," "You Never Can Tell," "Little Queenie," "Betty Jean," "Promised Land") along with the top-drawer tunes "Let It Rock," "Jaguar and the Thunderbird," "Down the Road Apiece" (actually a cover of Don Raye's 1940 boogie-woogie song although Berry re-wrote much of the lyrics), "La Juanda," and "Come On."

Initially, I found myself taken by "Jaguar and the Thunderbird," another of Chuck's road-racing songs, although it took me a few years to understand what "metaphor" meant and that this was his automotive equivalent to Lady and the Tramp. I also found "La Juanda," where love meets the language barrier, endearing—and I didn't need to know Spanish to recognize the missed signals Chuck encounters when he ventures south of the border. That's the U.S. border, by the way, although if Chuck had had a better grasp of Spanish, he may very well have ventured south of her border as well.

At the time of my Chuck Berry discovery, I was working as a mail clerk at a small company in California's Silicon Valley, and I regularly tormented my co-workers—all of us around the same age—with my homemade cassette recordings of vintage Chuck when they all listened to rock that was, shall we say, a little more contemporary. I listened to that as well, but I had already fashioned myself as a rock "historian," even a "scholar," and exploring Berry's catalog was such a revelation that I felt compelled to share it.

Our manager, Ray, was significantly older than we were, and even though he was the coolest boss I ever worked for, his musical tastes were decidedly different although he indulged our listening to rock. One time, I had to pick up a registered letter at the East Palo Alto post office. For those in the 21st century who might not be familiar with registered letters (let alone other antiquated devices such pay phones), they are typically sensitive documents that require the physical signature of the recipient—or a duly qualified proxy such as a pimply mail clerk who probably smoked a joint on his way to the post office—on the return receipt in order to be released and to show proof to the sender that the documents had been delivered to the recipient.

Now, I can't recall the exact circumstances here, as not only was this a while ago but, as suggested, I may have been smoking a lot of marijuana in those days. However, a few days later we learned that there was some kind of issue with the delivery, perhaps a dispute that it had actually been received by the addressee at the company, or at least within a specified time. Ray, who was ever-protective of his charges, began to bristle at the suggestion that we had made an error.

"I don't think we had anything to do with this!" Ray fumed. Then he looked down at a copy of the return receipt, which had the signature of the duly qualified proxy. "This wasn't even signed by any of us! It was signed for by—" He glanced down at the receipt, then had to hold it up more closely. "—Somebody named John B. Goodee! I don't think we even have anyone by that name in the company!"

At that point, I had to intervene. "Uh, Ray," I began. "I picked that up and signed for it the other day."

"But . . . " He frowned at me, puzzled. " . . . It says 'John B. Goodee.'"

"Yeah, I know. It's actually Johnny B. Goode." At this point, my co-workers listening in were beginning to snicker. "I signed for it with that."

"Why the hell—well, who's 'Johnny B. Goode'?"

"Er, it's actually the name of a Chuck Berry song." Then I felt compelled to add, "I didn't think anybody would be paying attention to the signature."

As my co-workers now laughed openly, Ray just rolled his eyes at me. Whatever the issue had been, it was a tempest in a teapot that passed without repercussions for anyone although I did get a short, albeit wry, lecture from Ray, and for the next few weeks any time I needed to sign for anything I got the smirking admonition from him to please, please, use my real name.

Although by the mid-1960s adulation greeted Chuck Berry for his mammoth contribution to the growth and development of rock and roll, he never strayed too far from that eminently influential model he had forged a decade earlier, and as rock music evolved Berry became part of its early history. Yielding three Top Forty hits ("Nadine," "You Never Can Tell," "No Particular Place to Go"), St. Louis to Liverpool remains Berry's signature studio album although The London Chuck Berry Sessions (1972), a half-studio, half-live affair made with members of Faces/Small Faces (the studio side) and the Average White Band (on stage), became the only Berry album to crack the Top Ten of the Billboard Top 200 albums chart while one live track, "Reelin' and Rockin'," reached Number 27 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart and another one, "My Ding-A-Ling," became Berry's only Number One single.

In between those two albums came a series of sets that gamely applied some contemporary trappings to his patented formula, with the most pointed songs offering reflections on Berry's real-life travails—the bluesy plea of "Have Mercy Judge," the wry, swinging string of denials in "It Wasn't Me," the relaxed if insistent declarations in "It's My Own Business," and the tremendous "Tulane," which crystallized all these themes, musical and lyrical, into a classic Chuck Berry shaggy-dog tale that celebrated the halcyon days in grand fashion.

Still, that was Berry's last gasp although he released three more albums in the 1970s. The title track of Bio, from 1973, was indeed the Chuck Berry creation myth, relating how he journeyed to Chess Records in Chicago, met his idol Muddy Waters, cut "Maybellene," and had the world fall at his feet, more or less, while the finger-snapping instrumental "Woodpecker" had a funky, loping swing not too far removed from the Meters. Chuck Berry (1975) was his final album for Chess and featured "A Deuce," which finds Chuck picking up a stoner chick at a party before getting it on in his car—truly matching his libido to the times. Berry's last album released before his death was Rock It (Atco, 1979), which reunited him with long-time collaborator Johnnie Johnson although by now Berry, a quarter-century removed from his heyday, seemed to be a relic from rock's primordial past.

To be sure, Berry had long been a fixture on the nostalgia circuit with a distinctive modus operandi: He showed up to concert just before he was slated to go on stage, expecting both to be paid in cash before going on and to have a local band already in place to back him. It didn't matter that he hadn't rehearsed with the band—he expected them to know his repertoire, and as countless garage bands have been cranking out Chuck Berry songs seemingly since time immemorial, it wasn't an entirely unreasonable expectation. Notable accompanists have included, besides the aforementioned Average White Band, Steve Miller and Bruce Springsteen.

But all that cash passing into Berry's hands had caught the attention of the Internal Revenue Service, and by 1979 it had caught up with him: Berry was convicted of tax evasion and served four months in the minimum-security facility in Lompoc, California, the same prison that had held convicted Watergate figures John Dean and H.R. Haldeman, and which inspired Berry to write the wistful if off-kilter "California," from Rock It. Not exactly the "Promised Land," but Berry did get to see the White House when President Jimmy Carter invited him to play there that same year.

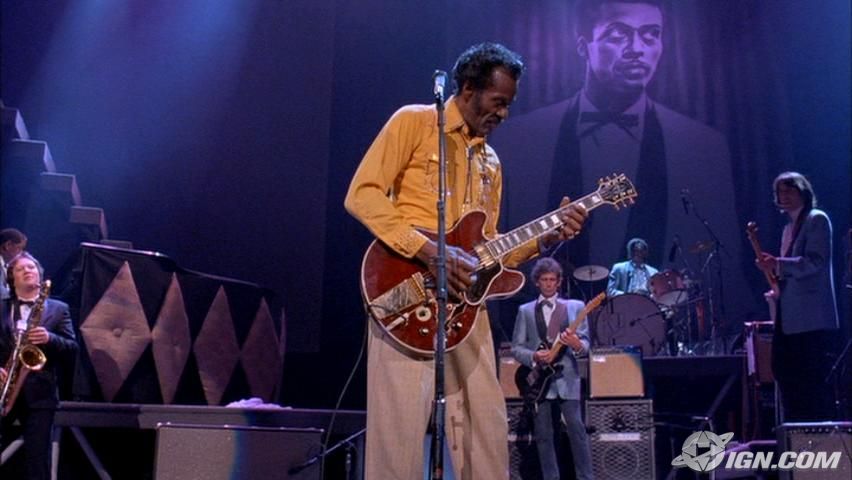

And for his 60th birthday, the Rolling Stones' Keith Richards, the world's greatest Chuck Berry-styled guitarist not named Chuck Berry, organized an all-star concert on Berry's behalf that director Taylor Hackford filmed as Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll, an eye-opening documentary that featured a glorious celebration of Berry's music onstage—spotlighting guests Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Etta James, and Linda Ronstadt—while underscoring offstage an irritable, disdainful, suspicious Berry who needed to exercise control of events at every turn—exemplified by pulling the plug on an interview segment with wife Thelmetta before she could even speak a half-dozen words.

The 1986 documentary Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll celebrated Berry's influence onstage but the behind-the-scenes looks could be less than flattering.

It risks becoming a cliché, that Chuck Berry was the golden idol with the feet of clay, but somehow his checkered personal life only makes his Promethean accomplishments seem more impressive—and in a most peculiar way, makes his story a distinctively American one. Amidst a middle-class upbringing, he runs afoul of the law and winds up in reform school, but upon his release, he starts a family and supports them while still pursuing his musical dream.

His passion, shaped by his broad musical palette, pays off as he becomes the Architect of Rock and Roll, a black family man who connects squarely with teenagers both black and white—no small feat in a time when blues and R&B discs are still being branded "race records," "colored music." He hits legal trouble again, this time with an underage girl, and winds up in prison once more, but when he emerges, he finds that his music has inspired the next generation of rock and rollers—while his contemporary Jerry Lee Lewis, who married his 13-year-old cousin, is chased from rock and roll and has to take refuge in country music.

Berry continues to have successes and setbacks, but he endures despite it all, and he finds that when the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 space probes were launched in 1977, each carried a golden record containing sounds, voices, and music from Earth—and his "Johnny B. Goode" is the only rock and roll song on the platter, chosen over stars such as Elvis Presley because Berry wrote the song in addition to singing and playing guitar on it.

It's no wonder that Berry also wrote "Back in the U.S.A," whose lyrics, ostensibly a paean to his home country, may in fact be ambiguous, that the "U.S.A." that he strove to embody in so many other timeless songs is an ideal that is reachable—"Anything you want, we got it right here in the U.S.A."—but that is also revocable—"Lookin' hard for a drive-in, searchin' for a corner café." Chuck Berry saw both sides of—pardon the hackneyed phrase, but it applies here—the American Dream, that on one side it is a fantasy to be fostered and on the other side it is an illusion to be shattered, a tricky proposition with even odds of success or failure. Berry experienced both and emerged a survivor every time.

In my musical education, just one facet of my journey through life albeit a rewarding and enjoyable one that continues to this day, Chuck Berry was the centerpiece of the core curriculum. Once I had discovered his seminal works, the very structure and fabric of rock music began to reveal itself to me because Chuck had provided its framework upon which countless others began to build.

Truth be told, Chuck Berry was never an artist who spoke to me personally, whose music struck a deep emotional chord as had other artists. Perhaps it was because his music seemed so universal, that it was so readily accessible to so many, that it was difficult to take it to heart.

In a sense, I liken it to learning the rudiments of English—grammar, syntax, punctuation, spelling—that I was impatient to learn as a kid, relying on intuition to help me skate over them, so I could get on with reading and writing. It wasn't until I revisited these rudiments as an adult that I grew to appreciate how vital they are, how they provide the framework upon which we build greater structures. Chuck Berry is vital to understanding how rock and roll was—is—put together. He provided the framework for it.

But in the last several years especially, as my own hourglass empties, I knew that when Chuck Berry died I would feel the sadness and loss. Even more so because as I've listened to Chuck's songs over the years, my appreciation of them has grown, particularly the ones that I didn't appreciate when I was younger because I lacked the maturity to grasp their emotional import—"Memphis"—or the discernment to grasp their pithy complexity—"Too Much Monkey Business." No wonder Keith Relf mumbled the words in the Yardbirds' cover version.

Chuck Berry arrived in my life a teacher who made learning fun—aw, Christ, he made learning a blast—and, once he imparted the lesson, he moved on, leaving me to build on the fundamentals he bestowed. And as the influential teacher, I returned to him periodically, grasping the lesson more keenly as I got older, appreciating the depth of his teaching as I understood it more clearly.

Perhaps it is like the relationship between "Johnny B. Goode," one of his greatest songs now speeding through interstellar space, and "Bye Bye Johnny," the answer record only Chuck Berry could have written.

When I was younger, "Johnny B. Goode" had the energy, the drive, the ambition of youth, whether it was Chuck's original, or Jimi Hendrix's incendiary live version, or Johnny Winter's cutting, precise version, or—hell—Marty McFly's spastic version disrupting the "Fish under the Sea" dance in Back to the Future.

Now "Bye Bye Johnny" has the emotionalism, the dramatic complexity, and, crucially, the concision to pack a wallop in its two minutes. It puts "Johnny B. Goode" into context and enriches it at the same time. More importantly, I'm ready for it now.

Chuck Berry is gone but he has never left me. And anytime I hear his locomotive roar, I'll be a-standin', a wavin' in the kitchen door.

Bye, bye, Johnny. Goodbye, Johnny B. Goode.

Comments powered by CComment